No, California isn’t going away, this is just the last photo from my recent trip down there. This is M78, captured with the SVX80T at f/6, and the ASI1600 camera. I shot the same target last year with the WO Star71, which has a significantly wider field of view, and also got it from the remote observatory in Australia with a somewhat narrower field of view. I’ve repeated the effort because none of these captures has been entirely satisfactory. This one is better than I expected given that it was captured in just 6 hours or so, over the last 2 nights I was there before having to pack up my gear. And the conditions were far from ideal, with lots of haze, marginal seeing, and sometimes even a small cloud drifting through the frame. After throwing out the worst frames, the trick to getting it to look this good is mostly in scaling it down to this size for display on the web! It’s not sharp enough for anything more than a “snapshot” print at 4 x 6 inches or so, but works fine for web display.

M78 itself is a combination of reflection and dark nebulosity, but this shot also includes some emission nebulosity in the lower left corner (red). This is a chunk of Barnard’s Loop, an enormous hydrogen molecular cloud that encircles most of the Orion constellation. This capture is entirely LRGB data (no narrowband), so this red band is surprisingly bright in comparison to the light blue reflection nebulosity. To the visual observer it would not appear this way, since our eyes are relatively insensitive to the H-alpha spectral line (a rather deep red), but the brightest portions of the reflection nebulosity (right around the stars that illuminate it) is easily seen, though not very colorful.

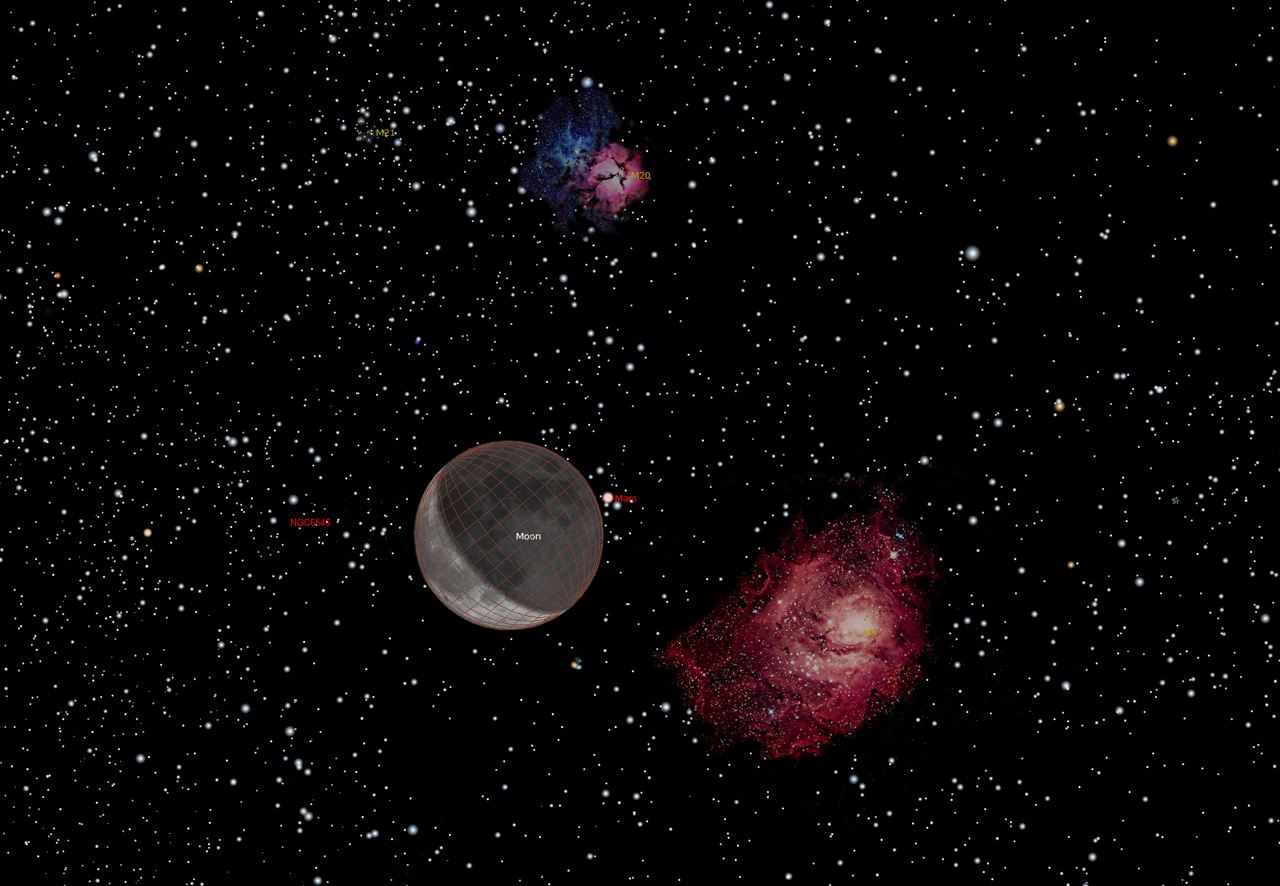

On another topic, we had a very interesting conjunction recently: In the early morning of February 18th, the Moon passed in front of Mars, and with M8 and M20 (Lagoon and Trifid nebulae) in the background. From here in the Pacific Northwest the Moon was below the horizon at the start of the occultation, and barely above the horizon at the end of it, around 4:30AM. So I knew I wouldn’t be able to get a good photo of it even if I was willing to set up all my equipment and wake up at 3:30. Fortunately, a friend who is still down in southern California was able to shoot it from there, where it was about 13 degrees higher in the sky. The difference in brightness between the Moon and the nebulae is so great that it’s pretty much impossible to capture them at the same time. Just capturing both the bright (sunlit) side and dark side of the Moon is tricky, and the nebulosity is much dimmer than the dark side of the Moon. So a “real” photo of the event will have to be a composite of shots done on different days. And since the background of M8 and M20 doesn’t change over time, that portion of the photo could be captured at any time, as long as you get the orientation right relative to the Moon and horizon. Here’s a simulation of what it would like like, from a planetarium program:

Wish I could have captured this!